The Trajectory of Fat Liberation: Where Did We Start? Where Are We Now?

Putting This Article in Context

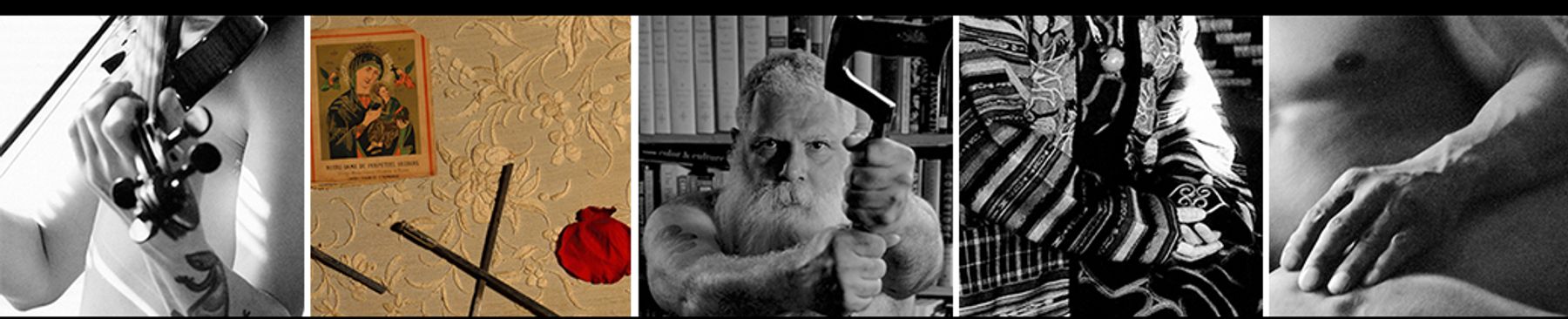

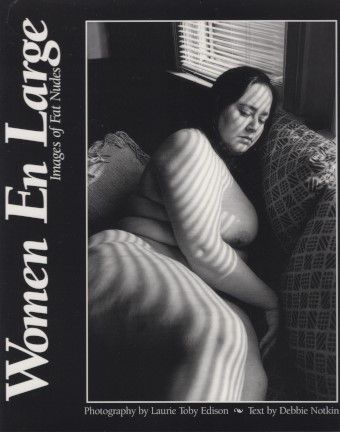

In 1994, Laurie Toby Edison and Debbie Notkin self-published Women En Large: Images of Fat Nudes, with Laurie’s photographs and text by Debbie. Working on that project embedded them deeply in the fat activist community, primarily but not only in the San Francisco Bay Area, at a time when the fat acceptance movement was taking shape. Some 27 years later, Women En Large, having been an independent press best-seller, is still in print. In this hybrid of first-hand participant observation, academic research, and popular culture analysis, the authors refer to themselves by their first names, to mark their closeness to the material.

In 1991, two years after Laurie opened her darkroom to print photographs of fat women, three years before Women En Large was published, we would never have dreamed of a reputable academic journal called Fat Studies. Or a Mattel line of dolls with “three different body shapes, seven skin colors, twenty-two eye colors and twenty-four hairstyles”(Douglas) Or that most people could name fat actresses who were neither comedians nor figures of fun.

Oppressions have both commonalities and distinctions; all oppressions have similar structures and widely varying intensities. Thus, fat oppression of white people, at its worst, is in no way as virulent or as dangerous as the white supremacist war on Black, Indigenous and Brown people, which can be exacerbated for fat Black, Indigenous and Brown bodies. One way to frame this exacerbation is through intersectionality. This term, initially articulated by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 to specifically describe the experience of Black women, is now used to analyze multiple simultaneous oppressions. While fat oppression is not comparable in intensity to structural and individual racism, intersectionality indicates that all oppressions take place alongside one another, and all resistance movements must contend with tension between primacy and coalition.

Ongoing marginalization, oppression, and silencing of any group happens simultaneously with increased resistance to invisibility. Generations and “waves” of feminism, anti-racism, disability rights all happen while crackdowns continue and often flourish. As an example, both the 1960s and the 1980s resulted in measurable gains for women’s political, social and cultural equality—albeit insufficient and incomplete. Disempowered groups, including women, people of color, disabled people, and more, have been contending against stigma for as long as they have been disempowered.

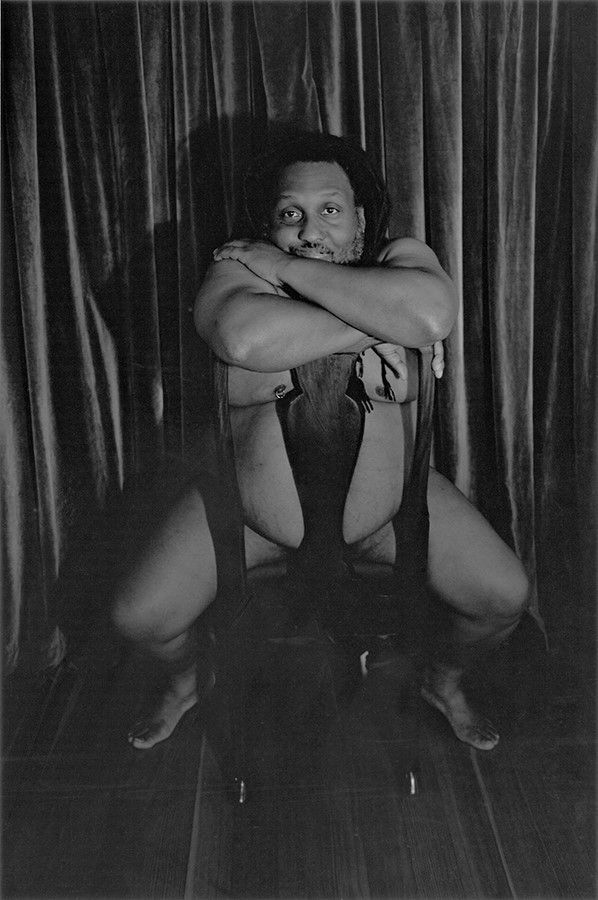

Chupoo Alafonté

Fat activism is unique among the uprisings and increased awareness of the 1960s and 1970s, because it has no obvious historic precursor. Specific policing of the size of women’s bodies is as old as male supremacy. Being lower in the class hierarchy leads to disproportionate oppression (being a poor person of color has an intersectional multiplier effect). Body image standards also fluctuate depending directly on whether women as a group are vocally asserting rights that the power structure will not concede. Women have been fighting their status for centuries. The beginning of an actual politics of fat, originally in the context of oppression of women, can be traced to the formation of the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance (NAAFA, 1969) and the more radical Fat Underground (1973) (Newman, p. 141).

Waxing and waning anti-racist activity has challenged white supremacy at least since the American Civil War, without erasing, silencing, or significantly disempowering the white supremacists’ grip on the United States. This mirrors, for most if not all social oppressions, continuing omnipresent opposition that is extremely resistant to change.

Rebecca Jennings, writing about social media and issues of fat and body size at Vox in 2021 astutely analyzes the presence of that opposition in the contemporary social media landscape:

At this point, it’s a cliché to even note that social media makes us feel like shit about ourselves. A series of studies has shown a correlation between activities like scrolling through Instagram and negative body image. A 2020 study of undergraduate women further showed that those who were asked to scroll through Instagram — but not Facebook, which emphasizes text more than photos — showed significantly decreased body satisfaction than those who were asked to do the reverse. (Jennings, 2021)

Social media – including its significant positive effects on members of marginalized groups – are addressed later in this article. Social media are not a universally negative force in fighting oppression; no cultural or social forces can generally be shown to succeed at dismantling the entrenched opposition.

Historically, in the face of mainstream and radical activism, the margins expand and the space to resist increases, but the centrality of the opposition remains inflexible.

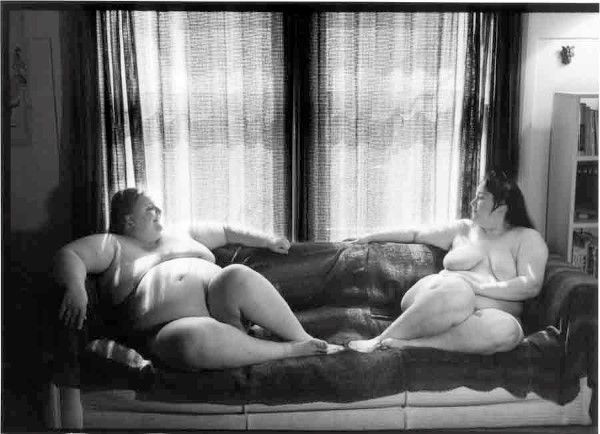

Tracy Blackstone and Debbie Notkin

The Late 20th Century: Putting a Dent In Fat Hatred

We began our personal journey to reclaim fat in the mid-1980s. While we conducted a series of panel discussions on the issue at science fiction conventions, Laurie, a lifetime professional jeweler and sculptor, began to see the beauty of fat bodies with her artist’s eye. She first made jewelry and sculpture depicting fat women’s bodies, but soon concluded that metal wasn’t the medium for what she wanted to express.

In 1988, she began taking photographs, starting with pictures of Debbie. In 1989, she opened her darkroom, and we embarked on a project that was to become Women En Large. The work linked Laurie’s fine-art environmental portrait photography of a widely diverse group of fat women with primary text by Debbie and supporting texts discussed further below.

We always knew it had to be a community project, so we organized a series of public meetings and conversations over five years. Laurie would show photographs and we would talk with the people in attendance about fat, body image, and health. We would then include in the book whatever subjects came up, which is how, among other choices, Laurie came to make images of fat women moving and exercising. In this period, we embedded ourselves in the burgeoning fat liberation and size acceptance movements. This gave us access to not only much of our material but also a deep and abiding commonality and understanding with the people (mostly women) who were and are essential to the fight against fat oppression. We could not have produced Women En Large, or done any of our other work, without that community. We were committed to making the work available as a book, so it could be accessible to the widest possible audience at a reasonable price.

We did not begin with an intention to self-publish this book; we submitted our book proposal to over 25 publishers, including feminist and photography small presses, and got rejections from every one, including some who told us that they loved the work but couldn’t take the risk of publishing such a transgressive project. At the same time, magazines and newspapers were paying attention. When the prestigious Utne Reader (back page) published a photograph with complementary text as their featured photograph, we decided it was time to get the work into the world quickly without a publisher.

We fund-raised the cost of publication from the same community that we had gone to for feedback and participation. We learned what we had to learn about paper quality, binding, press runs, and all the other big and small decisions that make a book – and in September 1994, we released our very first publishing project.

Every photograph in the book (and Laurie’s later portrait suites—Familiar Men: A Book of Nudes and Women of Japan) was taken in context. As Lori Don Levan wrote in “Resisting Negative Stereotypes of Female Fatness,” “Edison’s images are constructed through collaboration with the subjects where they have agency over the outcomes of the photographic act. Her creative process relies on her subject’s participation.” (Levan, p. 36)

As we continued the work, we —and the fat liberation movement—became more and more aware of the marginalization faced by fat men, exacerbated by the pressures on contemporary Western men not to engage with each other about shared pain and isolation. While Familiar Men is not about fat per se, Laurie did include fat models. Samuel R. Delany, noted writer and Familiar Men portrait subject, wrote:

I know my own bodily history: till 23, I was downright scrawny, and by 25, I suddenly started blowing up: some of my paternal uncles had done the same thing, so I assumed it was possible genetic. As far as I knew, there was no particular change in my diet, eating habits, or anything else. Aesthetics versus health is an old question in this discussion. Clearly health can be expanded to include much more weight than it usually does. (Samuel R. Delany, personal communication, 2021)

Riz R.

The photographs are carefully and aesthetically composed. Lesbian artist Tee Corinne wrote:

Because this is content-driven work it functions outside of the codifications and language of academic theories. The photographs are closer to documentary practice than to traditional art historical discourse … Women En Large expands the visual dialogue, the repertoire or catalog of stored images upon which aesthetic understanding rests. (Newman, p. 139)

These fine-art photographs have been exhibited internationally, including widely in Japan, and also in (among other cities) London, Budapest, Shanghai, Seoul, Barcelona, and Rome. Our experience is that Laurie’s rapport with the people in the photographs and her commitment to avoid “othering” create a final product that viewers find welcoming rather than shocking. Many Japanese viewers, despite a certain amount of acculturation that demonizes fat bodies, have told Laurie that the photographs are “comfortable.” Our 2009 article in Asia Pacific Journal; Japan Focus “Body Image in Japan and the United States” contains much more detail on our work in Japan and what we learned there.

We always knew the final project had to be diverse enough for most women to be able to see themselves in the photographs. We used the community meetings, and our connections, to solicit women who might want to be photographed. The book includes women of color, disabled women, older and younger women. The suite of photographs grew and got richer. In 1994, six years after the project began in earnest and six months after we committed to self-publishing, the book was released. The book includes not only Laurie’s photographs and Debbie’s essays, but many texts and some poetry from the women in the photographs, and other women with different perspectives on the topic. The photographs are rarely exhibited without including the voices of models and allies, just as we include those voices in this text. Women En Large is still in print 27 years later, with well over 10,000 copies sold.

Kathleen LeBesco’s analysis of the book’s intent is insightful: “[Notkin]’s text is intended less to radically revamp society’s perception of fat bodies than to aid fat women in feeling better about themselves” (Newman, p. 143). Revamping society’s assumptions is a decades- or centuries-long project that cannot be undertaken without revamping the internalized experience of the people harmed by those social stereotypes.

As indicated above, fat activism preceded us, not only with NAAFA and the Fat Underground, but also in key publications and performers. Fat liberation was a full-fledged movement before we got started. Susie Orbach publicly reclaimed the word “fat” in her best-selling Fat Is a Feminist Issue: the anti-diet guide to permanent weight loss, published in 1978. On that book’s 30-year anniversary, Orbach described the cause as a failure, a perception we will examine further.

… we never saw the backlash coming, or the ingenious forms it would take, from the now rather innocent (“Because you’re worth it”) to the downright nefarious practices of industries that were growing rich on the making of body insecurity. And that was way before social media and the beauty bloggers with their, yes, millions of followers, would begin to reap money as daily beauty labor …. Beauty work became relentless and, with it, the ubiquity of … judgments and failures which, once internalized, destabilized girls’ relationship to their bodies and – as if that wasn’t enough – created an insecurity that hurt their minds. (Orbach, 2018)

The far more radical Shadow on a Tightrope: Writings by Women on Fat Oppression, edited by Lisa Schoenfielder and Barb Wieser, was published in 1983. These two books demonstrate the range of early fat liberation. Orbach’s mainstream work with its weight-loss subtitle was published by a small press but quickly picked up by a mainstream publisher and available everywhere in airport-size paperback; Schoenfielder and Wieser were published in the Lesbian small press universe and stayed there, with a 30th anniversary re-issue in 2013.

Tightrope stems from the work of the Fat Underground and demonstrates the courage and power of Lesbian feminists in the early 1980s. It is shamefully but not completely white-centric, covering topics ranging from memories to exercise and sport to harassment to dieting. Here is Vivian F. Mayer, writing in the foreword:

The pain of fat women is no secret. Recently, some popular books have dwelt on it at length, adding perhaps to the puzzlement as to why they stay fat. However, the pain is rarely expressed unequivocally, in our own words. One of the remarkable things about this book which you are about to read is that, in it, fat women talk about their pain unequivocally. Without covering it up with excuses such as “they mean well, they’re only trying to get me to lose weight.” Strong women have no use for excuses.

The strength of fat women is not so well known. But as you read this book you’ll come to know it. And if you’re fat, in case you haven’t yet seen the strength in yourself, I promise you, you will. (Schoenfielder and Wieser, 1983, p. ix)

These pioneers, and many other allied groups and publications, all collaborated in building new and necessary language necessary. As an historic first identification of a specific oppressed group, early activists borrowed some language from the civil rights movement, the nascent disability rights movement, and the long history of feminist movements. They also developed new language to discuss the specifics of fat, to counteract words like “overweight” and parry inevitable vicious insults such as “whale” or “blubber.” One way to frame our work is as a very early contribution to the visual language that is, when done well, always more powerful and effective than verbal language.

San Francisco’s Fat Lip Readers’ Theatre, a lineal daughter of the Fat Underground, was a source of cross-fertilization, mutual critique and learning for many years. Performing in Fat Lip, fat women embodied their stories publicly at many women’s music festivals, street fairs and other venues. Laura Bock and Carol Squires wrote about the group in “Fat Lip Readers Theatre: A recollection in two voices”:

Fat hatred is deeply ingrained in the United States. The profit motive of continually creating new diets, medications, or surgeries to make fat people thin is deep-rooted. In addition, we have decades of the media telling us, especially women, to be thin is to be pretty, and being pretty is the key to a happy life. FLRT was a group of fat women, standing in the spotlight, loudly and unapologetically proclaiming, “We are fat, deal with it!” I believe we created a ripple of fat positivity that touched many people. So, while we didn’t destroy fat hatred, I do believe we put a dent in it. (Bock and Squires, 2019, p. 236)

When we and our allies were getting started, literally the only mass-market clothes available to fat women in the United States were from Lane Bryant, a nationwide chain still in business in 2021. Their selection was overwhelmingly polyester, usually large flower prints and designs catering to older, more suburban aesthetics—“feminine” without sexiness or desirability. Emerging small companies, often founded by fat women, featured fat models, large sizes (sometimes up to 5X and 6X), natural fabrics and stylish design. Today a fat teenage girl can probably find clothing to suit her in most department stores, and can certainly find many choices, some comparatively affordable, online. Activists may decry consumerism and the profit motive, and yet those factors made the difference for hundreds of thousands of women who just want attractive clothes that fit.

Carol Squires, who is photographed in Women En Large and co-wrote the Fat Lip quotation above, tells an all-too-familiar story from that time:

I was at a science fiction convention. A fat woman came up to me and said she’d seen me perform a couple of years earlier. She asked if we could go somewhere private to talk. Almost as soon as we were away from the crowds, she started to cry. She confessed how much she’d always hated her fat body and blamed it for all the trouble in her life, including a series of abusive relationships. Our words had planted a seed. She hadn’t given up the quest for thinness, but she had taken to the heart our messages: Don’t put your life on hold until you get thin, and you deserve respect and happiness no matter your size. She’d recently ended a relationship with a man who confessed he had to keep his eyes closed when they were having sex because her fatness grossed him out. Previously, she’d hung onto relationships like this until the other person left. This time, a month into dating him, she cut him loose. We cried, we laughed, and we hugged. I never saw her again, but I like to think she eventually made peace with her body. (Carol Squires, personal communication, 2021)