50代である私にとって、写真に写る自分の姿を見ることは、「哲学的」とでも言うべき行為である。私はこの20年間、大学教員として、またもの書き として、フェミニズム思想と視覚文化を追究して過ごしてきた。容貌の美醜という問題が女にとってただならぬ重さをもっている現実も、そういう現実が維持さ れる理由も、またその問題が女への制度的抑圧であることもよく承知している。だから私自身は、そういう現実への抵抗として、自分の容貌については能動的な 無関心という態度を選択してきた。

それがこのたびエディスンと出会って、被写体となり。写真に写る自分の姿と向きあうはめになってしまった。加齢と容貌の相関関係は、残酷であるが誰 にも平等に起こることだ。受け入れがたいことではない。それよりも私に「哲学的」省察を促すのは、50年ほどのあいだに自分が背負いこんだもの、自分が来 た一様でしかない道が、不寛容な険しさとなって写真のなかの私の相貌全体に刻みつけられていることをつきつけられるからだ。京都は修学院荘の閉じた門扉の 前に立って、私は両腕を広げている。撮影時にはたいした意味もなかってつもりのその所作が、数十枚のなかから写真家が選んだ1枚では、私の50年を表わし ていると読めてしまう。ここで私が両腕を広げて懸命に護ろうとしているものは何なのか。何から護ろうとしているのか。私は何と対決しているのか。こうでな いあり様はなかったのか。これらの問いは、私にとってしか意味がない。つまりこの写真体験はごく私的なものだ。

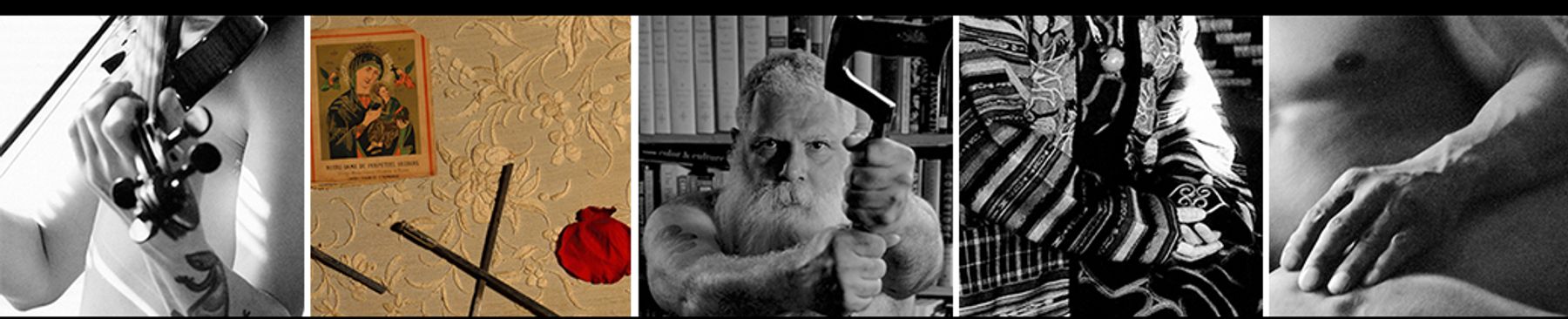

ところがそんな私的な写真が、特定されない未知の観者に向けて展示され、加えて Women of Japan という表題がつけられている。表題は写真の外にあるものだが、観者が写真に何を見るかを決めるうえで重要である。ここで私は「日本の女」のひ とりである。法的地位としては、私は生来から日本国籍を有する日本人であり。日本と呼ばれる地で日本語を母語として暮らしている。思想的立場としては、 「日本」という括りを自明のものとして自足するのではなく、その括りからはみだして生きる可能性を追求している。そうすることで、「日本」で生きる日本人 の特権を批判的に相対化したいと思っている。それだけにエディスンのシリーズ写真のなかでは、他の「日本の女」たちに比して、「日本」からはみだしていな い自分を確認させられる。「日本の女」は、「日本人の女」を拒否して選ばれた表題である。しかし、私の写る一枚は「日本人の女」をどれだけ拒否したもので あるだろう。むろんこれは写真についての問いではなく、自分についての問いだ。

こうしてエディスンは、終わらない問いに被写体を直面させる。社会変革のための芸術をめざし、被写体を対象物化しないという彼女の創作の姿勢が、被写体である私にも伝播して、共有されたということである。

As a woman over fifty to see my own portrait is a sort of metaphysical act. I have spent some twenty years, as a writer and university lecturer, working on feminist ideologies and issues of politics around visual cultures. I know fairly well about the fact that the issue of physical beauty is more critical for women than for men. I also know why and how things are so, and how beauty politics works as institutionalized oppression against women. So, in resistance, I have been intentionally unconcerned about my appearance.

I met Edison and posed for her to take my portrait. I had to face my features in the picture. I was ready to see how aging would unavoidably affect my looks. Because that happens to everyone, I am receptive of my own case. Rather, I am urged to have a metaphysical reflection by what the photographer captures beyond my expectation. It is hard for me to ignore the signs of intolerance and rigidity, which have been inscribed in my facial and body expressions in the course of my irrevocable fifty years. Here I am standing in front of the closed gate with my arms outspread. The pose the photographer selected out of many rolls of film seems to imply my whole life. What am I defending and from what? What am I facing? Could I have taken alternative ways? These are the questions which are significant only for me. Seeing my portrait starts as a purely personal experience.

This personal portrait was intended to be shown in public. It is shown under the title “Women of Japan” along with images of other women with diverse national and social backgrounds. The title is an appendage to the photographs, but it plays a decisive role when an audience reads the images. In Edison’s work I am one of the “Women of Japan.” I am a Japanese national by birth and a native Japanese speaker, living in the land geopolitically called “Japan” and holding a legal status fully approved by the authorities. Ideologically, I have always tended to be off “Japan” as a fixed categorization so as to play down and be critically objective of the cultural and political privileges of “being Japanese.” Here, however, I consider my image one of the least ‘off’ Japanese. Naming this series of portraits “Women of Japan” is Edison’s negation of “Japanese Women,” which could have easily been the expected title. But how much does my image negate “Japanese Women”? This is, of course, a question not about the picture but about myself.

Edison always tries to treat the sitter not as a “still” model but as an active partner co-working for her project. She urges the photographed to face an unceasing chain of questions. That is how her art for social change is shared.

translation by the author